Jacopo da Trezzo

Jacopo da Trezzo (c. 1515 or 1519 – 1589) was an Italian Renaissance sculptor of medals and jeweller, who after beginning his career in Milan moved to employment by the Spanish Habsburgs in 1554. He spent the rest of his career working for the Spanish court, beginning by visiting England in 1554–55 during the marriage of Philip II of Spain and Mary I of England, which lasted from 1554 to her death in 1558.[1]

He was born Giacomo or Jacopo Nizzola (or Nizola), sometime between 1514 and 1519, in Trezzo sull'Adda, then a village some 30 kilometres (19 miles) northeast of Milan on the Adda River (now included in Milan's Metropolitan region). In Spain he became known as Jacometrezo.[2] In Brussels in the 1550s he signed documents as "Jacobo" or "Jacomo da Trezo".[3]

He is probably now best known for his eleven medals, probably produced between 1548 and 1578, in Italy, England and Spain.[4]

Biography

[edit]His birth date is uncertain; the earlier 1514–1515 date comes from a reference in a letter, much later, where he says he entered the service of Philip when he was 31. His father Gaspare was described as magister or "master", indicating some professional or social status. The family were living in Milan by 1531. He trained with a carver of engraved gems and hardstone objects in Milan.[3]

By the 1540s he was a successful artist, mostly based in Milan, his patrons including Cosimo I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, who paid him in 1550–52 for two large vessels, a vase and a cup, in rock crystal (quartz).[3] He received a mention in the first edition of Vasari's Lives of the Artists (1550). Milan was ruled by Spain, and the home of Leone Leoni, master of the mint there from 1542, and the main producer of large portrait sculptures for the Habsburgs. He had made medals for the Habsburgs, including one of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor in 1536. But by the 1550s Leoni's interest had moved on to life-size portrait sculptures. In the past there has been some difficulty distinguishing between Leoni's work and Jacopo's.[5] Jacopo may well have assisted with coin dies at the mint, but this is not documented.[3]

It was probably through Leoni, or Vasari, that the Habsburgs became aware of Jacopo da Trezzo, who in 1554 was summoned to join their service, apparently starting by travelling to England, where the future Philip II of Spain married Mary I of England on 25 July 1554, two days after their first meeting. Jacopo produced medals to commemorate the marriage, modelling two portrait faces and two allegorical reverses. These were cast in versions with the two heads, one on each face, and more conventional ones with the obverse and reverse relating to each of the couple. They survive in a variety of metals, from lead to gold.[6]

Late in 1554, Jacopo sent Cardinal Granvelle in Brussels, in effect the Habsburg's foreign minister, the medal of Mary in silver,[1] but Philip's medal is dated 1555. The ones with a head on each side are "an unusual combination and recast of two earlier independent medals", perhaps from 1555.[7] One of only two known examples in gold of Mary's medal sold for £130,250 at Christie's in 2000.[8]

It was therefore after Mary's marriage medal was produced when on New Years Day 1555 Jacopo was appointed court sculptor (escultor) to Philip in London. In 1555 he followed Philip to Brussels, capital of the Spanish Netherlands, staying until at least 1559. By 1562 he was in Madrid, where Philip was now King of Spain.[3] He seems to have remained there for the rest of his life, dying there on 23 September 1589.[1]

Works

[edit]

None of his jewellery (in the normal sense of necklaces etc.) is known to survive; it is possible that he made some of the rich jewellery worn by Mary I in her portrait by Anthonis Mor in the Prado Museum, and other Spanish court portraits of the period.[5] He was known for engraved gems, some of which survive. While in Brussels he made, but did not design, Philip's "great seal", in use by 1557, and engraved a diamond with the coat of arms of Charles V, who also paid him in 1556 for a rock crystal drinking glass.[9]

In Madrid he made various hardstone carvings and cameos for the court, but these were generally not signed, leading to some uncertainty in attributions. He was used by the royal family to value and negotiate purchases of similar items, as well as antiquities. He also acted as a dealer, in 1584 selling Philip the Annunciation by Robert Campin now in the Prado, for El Escorial. He worked for other courts as well; works for the Medici, the court at Parma, and the Austrian Habsburgs are recorded.[10] His workshop was visited by the royal family and court.[11]

With Pompeo Leoni and another artist he executed the tomb monument for Joanna, Princess of Portugal (d 1573), Philip II's sister, in the church of the Convent of Las Descalzas Reales in Madrid, which she had founded in her parents' palace in 1559. To a design by the architect Juan de Herrera he made the tabernacle for the main altar in the church of the monastery of El Escorial (1586), in gilt-bronze, rock crystal and coloured hardstone.[3]

He, or his workshop, may have carved the lapis lazuli cameos of the Twelve Caesars that were (probably later) incorporated round the border of an elaborate platter in engraved rock crystal, gold, gems and enamels. This is now part of the "Treasury of the Dauphin" in the Prado Museum.[12]

Medals

[edit]Early medals made in Italy included those of the wife, Isabella di Capua, and daughter Ippolita (1535–1563) of Ferrante Gonzaga, then Governor of the Duchy of Milan, made in about 1552. Both are signed at the bottom of the portrait ("IAC.TREZZO" on the former and "IAC TREZ" on the latter). His medal of Mary of Hungary, sister of Charles V, dates from c. 1549–51, and that of her niece Princess Joanna of Portugal, Philip II's sister, from 1554. Gianello della Torre, an engineer and clock-maker from Cremona, was another Italian who worked for the court in Spain, and his medal appears to date from Jacopo's first years in Spain.[9]

The marriage medals of Philip and Mary (discussed in the previous section) were repeated in oval versions, showing only their heads, and much later Philip was again portrayed in a similar round medal. Other medals were of Ascanio Padula (1577), as the inscription says an "Italian nobleman",[13] and the architect Juan de Herrera (1578),[14] the Grand Inquisitor Diego de Espinosa (1568), and the Austrian ambassador Hans von Khevenhüller (1577), a neighbour in Madrid,[3] who helped arrange some foreign commissions, as did the medallist Antonio Abbondio.[11]

-

Reverse of the marriage medal of Mary I, inscribed CECIS VISVS TIMIDIS QVIES - "Sight for the Blind, Tranquility for the Fearful".[15]

-

Philip II, his medal for the marriage with Mary I, dated 1555

-

Reverse of Philip's medal: Apollo and the Chariot of the Sun.

-

Gianello della Torre, late 1550s

-

Reverse of Gianello della Torre's medal, allegory of Virtue

Portraits

[edit]

An unusually intimate portrait by Anthonis Mor, probably painted in Brussels in 1555–59, was sold by Sotheby's in London, on 4 December 2019 for £1.93 million. Another portrait is known to have belonged to Philip but is now lost; it showed "the celebrated sculptor beside the tabernacle he executed for the high altar of the basilica of San Lorenzo at the Escorial". Another, also lost, is recorded as by Bernardino Campi of Cremona, presumably painted before he left Italy. A third, showing a much older man, is attributed to the Spanish court painter Alonso Sánchez Coello, perhaps around 1580.[1]

There is also a medal of him, by Antonio Abbondio, dated 1572.[3] Abbondio was another Italian emigre medallist, who mostly worked for the Austrian Habsburgs.

Slaves in the workshop

[edit]Queen Catherine of Portugal, a sister of Charles V, followed the custom of the Portuguese court and had a considerable number of slaves in the royal households, at this period mostly from modern Brazil, but some from Portuguese Africa. They were generally well-treated and some trained in various skills, but were also treated as chattels, and sometimes presented as gifts; others were manumitted.[16]

In 1554 she sent her grandson in Madrid, Don Carlos, heir to the Spanish throne, three slaves. By 1564 two of these, Diego de San Pedro and Juan Carlos, were being trained in Jacopo da Trezzo's workshop, and he was later paid for their food and clothes by Carlos' household.[17] According to Don Carlos' will of the same year, they were to be freed on his death, which came unexpectedly early in 1568. Philip II later confirmed the manumission. Payments to Jacopo are only recorded in 1568, relating to expenses in 1564 and 1565. The later history of the pair is unknown.[17]

Legacy

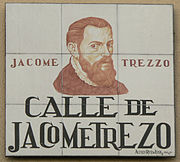

[edit]The calle de Jacometrezo is a street in central Madrid named after him, with a pictorial street sign based on the Mor portrait, and there is a plaque on the Casa Matesanz, Gran Via 27, Madrid, recording the site of the house he lived in.[18]

-

Attributed; topaz carved with portraits of Philip II and his son Don Carlos, c. 1566, Cabinet des médailles, Paris

-

Tabernacle for the church of El Escorial, 1586

-

Street sign, Calle de Jacometrezo, Madrid

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Sotheby's

- ^ Sotheby's; Rossi. As with many dates relating to Jacopo, various dates appear in different sources.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cupperi

- ^ "Jacopo da Trezzo" bio, National Portrait Gallery, London "Between 1548 and 1578 Jacopo produced eleven medals, including variants, eight of which are signed."

- ^ a b Rossi

- ^ Sotheby's; Cupperi; Example of the Mary I medal in lead, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ "Portrait medal of Philip II (obverse); Mary Tudor Queen of England (reverse), 1555", silver example in the Metropolitan Museum]

- ^ Lot 36, Live Auction 6407, THE COLLECTION OF THE LATE BARONESS BATSHEVA DE ROTHSCHILD, Christie's, London; the other is in the British Museum, the one illustrated here.

- ^ a b Sotheby's; Cupperi

- ^ Cupperi; Tudela; Prado page on the Campin

- ^ a b Tudela

- ^ Prado page on the platter (in Spanish).

- ^ Example in the National Gallery of Art

- ^ Example in the National Gallery of Art

- ^ Metropolitan Museum page

- ^ Jordan, 155–173

- ^ a b Jordan, 174–175

- ^ photo of the plaque

References

[edit]- Cupperi, Walter, biography "Nizzola, Giovan Giacomo", in Dizionario biografico degli italiani, 78, 2013, Treccani (in Italian)

- Jordan, Annemarie, Chapter 7 in Black Africans in Renaissance Europe, K. J. P. Lowe, T. F. Earle eds, 2005, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521815826

- Rossi, Filippo, IACOPO Nizzola da Trezzo , Enciclopedia Italiana, 1933 (in Italian)

- "Sotheby's": Portrait of Jacopo da Trezzo (c. 1514–1589) by Anthonis Mor, Sotheby's, Lot 22, Old Masters Evening Sale, London, 4 December 2019 (sold, £1.93 million)

- "Trezzo", "Jacopo Nizzola da Trezzo", Il Portale di Storia Locale è di proprietà del Comune di Trezzo sull'Adda (Milano), biography on the municipal website of his birthplace (in Italian).

- Tudela, Almudena Pérez de, biography, Real Academia de la Historia (in Spanish)

External links

[edit]- NGA, 16 images

![Reverse of the marriage medal of Mary I, inscribed CECIS VISVS TIMIDIS QVIES - "Sight for the Blind, Tranquility for the Fearful".[15]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/32/Mary_Tudor%2C_Queen_of_England_%281516-1558%2C_r._1553%2C_m._1554%29%2C_Commemorating_her_Marriage_to_Philip_of_Spain_%281527-1598%2C_r._1556-98%29_MET_109167.jpg/170px-Mary_Tudor%2C_Queen_of_England_%281516-1558%2C_r._1553%2C_m._1554%29%2C_Commemorating_her_Marriage_to_Philip_of_Spain_%281527-1598%2C_r._1556-98%29_MET_109167.jpg)